Community art bridges tradition and contemporary expression in this northern province

Art is deeply imbedded in the culture of the Buscalan village in Kalinga. After all, it is the place that produced Apo Whang-Od, the world-renowned mambabatok visited by tourists from the world over. But given the typical effects of intercultural exchange via tourism and globalization, there’s the constant threat of local cultural values getting diluted and eventually disappearing in the name of progress and modernization.

But if Archie Oclos had his way, community art can guide everyone towards finding balance between the traditional and the contemporary. The Cultural Center of the Philippines 13 Artists awardee initiated a socially engaged art project involving a team of street artists, cultural workers, and art practitioners that aims to reach different communities in various parts of the country in a cross-cultural immersion. Their first stop was Buscalan, which they visited earlier this month.

“Sa Buscalan muna dahil buhay na buhay ang komunal na kaisipan ng mga lokal dun,” Oclos explains. “Modernisado man silang tingnan, naka-ugat pa rin sila sa mga tradisyunal na paniniwala at pamamaraan sa buhay. Magandang kundisyon din iyon upang mamulat at matuto ang mga artists sa mga tao ng Buscalan dahil sila ang tagapagturo at may akda ng kanilang kultura.”

For the four-day immersion, Oclos put together a team that included Kris Abrigo, Bvdot, Jenn Ban, Doktor Karayom, Ralph Eya, Ilona Fiddy, Dee Jae Pa’este, Kookoo Ramos, and Sim Tolentino, and the group created 11 artworks that represent their respective cultural experiences and creative styles.

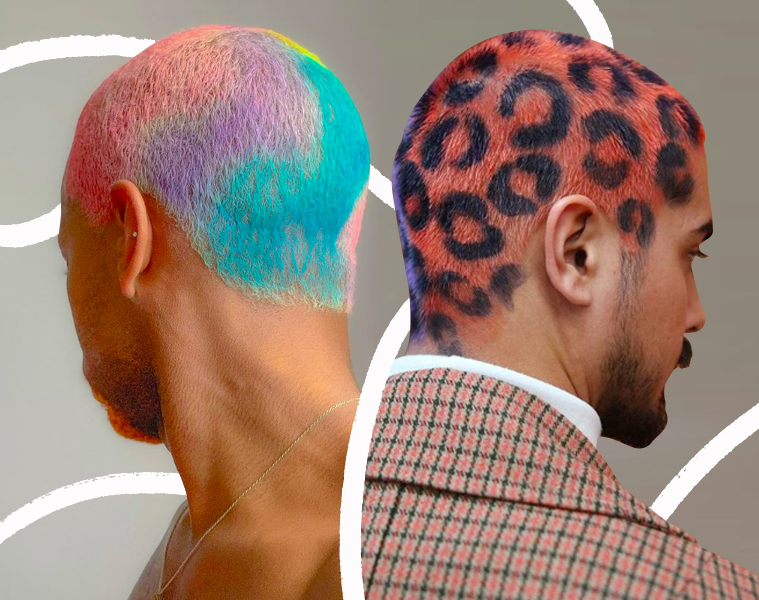

For Bvdot’s “Tagpuan,” he used both his experiences and the story of Kalinga’s Nanay Ampit and the Butbut tribe as inspiration. “Working and immersing with the local community made me realize that wherever we go, we must respect each other’s traditions and ways of life.”

“It is important for us to know our place in a ‘foreign’ place,” Doktor Karayom agrees. “Just because people live up here in the mountains doesn’t mean they know less than us city dwellers. I feel that the people here actually know what living means more than us.”

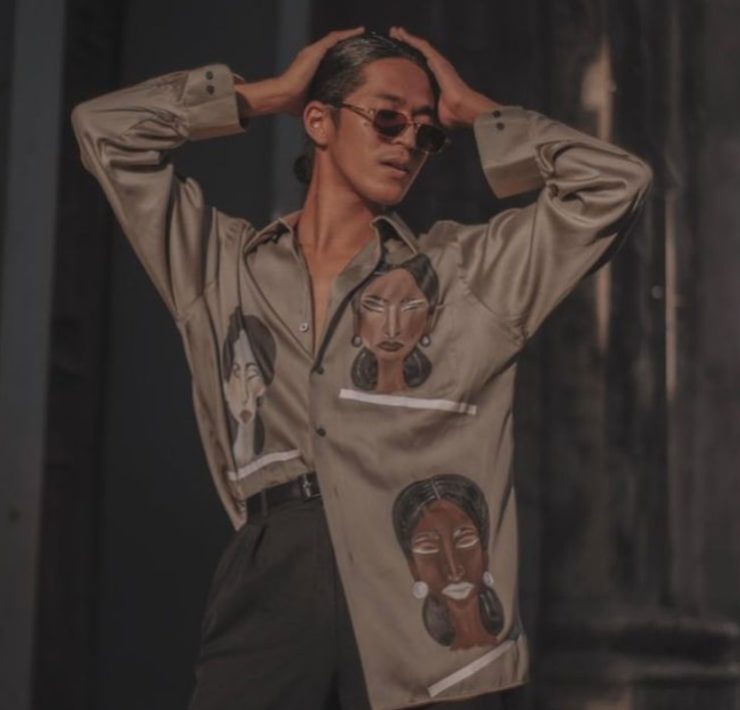

Muralist Kookoo Ramos’ exposure to community work was similarly crucial to her art process, as the quotidian elements of the local lifestyle—dried plants, wooden items, hunting and farming tools—served as visual inspirations. It was the role and significance of local women to the community, however, that provided her with a different perspective: “From what I saw in Buscalan, the role of women was simple but truly relevant. Tunay silang ilaw ng tahanan; no need for me to exaggerate, twist, or create a more aesthetically appealing statement piece. I found value in that simplicity—the value of taking care of the people, the community, and the next generations to come.”

For the mural he created at Buscalan’s barangay hall, Kris Abrigo intended to contribute to the community design by highlighting the relationship between local institutions and their purposes and the people. “It’s about transforming basic local concrete architecture into something that represents the people, and reflects the place around it, focusing only on the essential, recognizable, and significant objects that the viewers can relate to.”

“There will always be a burning passion within artists to create a greater impact on society,” art practitioner and advocate Ralph Eya states. He sees the project as living testament of what artistic production, collective action, and active social participation can achieve. “It is just a matter of someone igniting that spark and taking on the challenge of leading our fellow creative practitioners to progressive and meaningful collaborations—and that’s the spirit of community art. It is not just about murals or artworks placed in a community setting, nor just another buzzword we lightly use in art practice. It is about co-creating. It is about evolving together. Community art is activism.”

Oclos sees his and his fellow artists’ role as the bridge where heritage and modernity could meet with equanimity; his mural, in particular, is based on how locals would bring commercial products from the city up to the mountains. “The people here know that they need those products to sustain their living, but in the process, they also recognize that they too become dependent on the existing system of commerce,” he says. “We need to acknowledge the sentiments of the members of the community. We are just messengers of their causes.”

With the murals located in different pockets of Buscalan, there’s a vibrant pop of color to encounter at almost every turn. More than aesthetics, though, the artworks are a celebration of local culture and identity, and how rich, layered, and vibrant it has become through generations of cultural exchange. With the Kalinga village as the first stop, the group hopes to create a ripple effect among like-minded artists, community leaders, cultural workers, stakeholders, and the youth all over the country and encourage them to start similar initiatives and deeper conversations on the intersection of art, culture, and social progress.

Header image features art by Bvdot. All images courtesy of Jenn Ban