Chiffon shirts and sprezzatura at the New York Men’s shows

NEW YORK – It is too soon to trumpet another golden age, as journalists rushed to do the last time New York designers gathered under one tent for a week of shows and presentations dedicated to menswear.

NEW YORK – It is too soon to trumpet another golden age, as journalists rushed to do the last time New York designers gathered under one tent for a week of shows and presentations dedicated to menswear.

It was back in 1995 that Seventh on Sixth – the nonprofit that had mounted the successful women’s fashion weeks here under tents in Bryant Park since 1993 – recruited 23 designers to make the case that store buyers, the press and, most important, consumers were primed to treat fashion as an alluring new form of mass entertainment.

No one can say with authority why those efforts sputtered out after a relatively short time, done in perhaps by casual Friday or the aftereffects of Sept. 11 or just a generalized caution among men about signing on wholeheartedly for anything as girlie as fashion.

That was then.

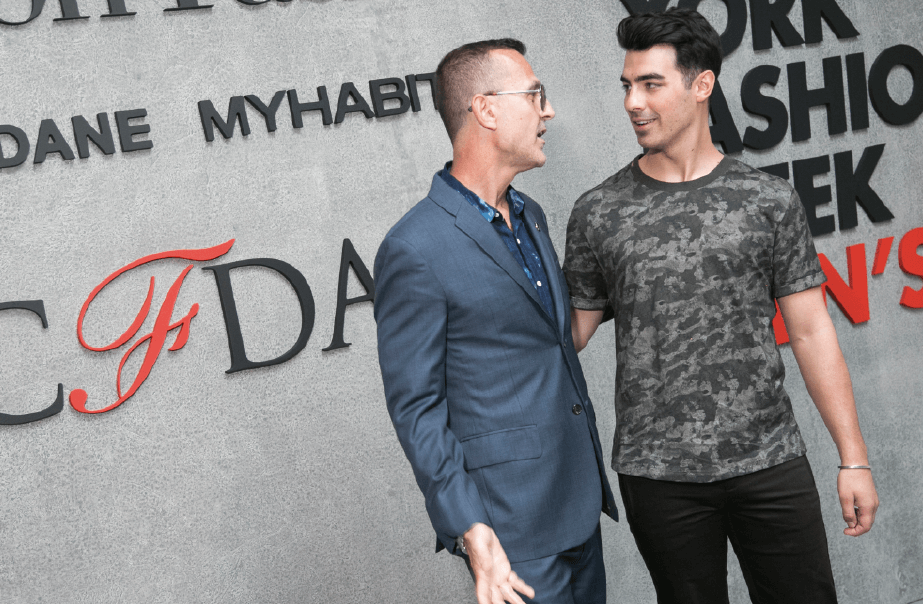

Roughly three score designers are showing here this week in a revived New York Fashion Week: Men’s, and they do so at a time when the Internet has radically altered the rules of engagement; when an industry veteran like 56-year-old Nick Wooster can suddenly find himself a cult Instagram figure, featured on magazine covers and marketed in Asia as a kind of living style cartoon; when athletes and actors compete to be seen wearing designer clothes in the front rows of fashion shows; when men in general seem eager to participate in their own objectification (the trending Yahoo topic as the week began? “Jason Statham flaunts his abs”); when mainstream companies like Amazon, Cadillac and DreamWorks detect brand-building opportunities in sponsoring events centered on handsome lugs parading around in organza T-shirts or flap-pocket shorts of delave linen.

We are in a period when, as one paparazzo remarked Tuesday, “There are even street style photographers now in small jungle villages in Honduras.”

He wasn’t kidding. Scott Schuman, Sartorialist blogger, has set about making himself the National Geographic of style.

“I’m so glad we got a divorce” from womenswear, said Ronen Jehezkel, a designer for the sportswear label Parke & Ronen, referring to the practice in recent years of folding menswear shows into the ballyhooed women’s fashion weeks. “It will take a year or two to get used to being single,” Jehezkel added. “But this time I think it’s going to work.”

Early evidence suggests he’s correct.

It is not that any breakout talent suddenly appeared to send the roof of the industrial space Skylight Clarkson Sq in lower Manhattan – in which a majority of the shows are being held – spinning skyward. While most hewed to familiar design briefs and embraced the reassurance of established “brand identities,” as Timo Weiland said of his quiet collection of garments with patterns based on television screen static for a generation that wouldn’t know a suit from a pair of rabbit-ear antennas, there was still enough creativity and moxie to support the proposition that New York is prepared to compete again with the European design capitals that for most of the past decade have eaten its lunch.

There was, standing apart from the pack, Duckie Brown.

At the end of last season’s show, the label’s designers, Steven Cox and Daniel Silver, dejectedly told journalists they would likely be forced to shutter the brand. Lucrative collaborations with big manufacturers they had long used to subsidize their own label had dried up.

“You can’t do this on air,” Silver had said.

Yet like exotic air-breathing epiphytes, Duckie Brown somehow survived. And the beautiful show for spring 2016 they presented Tuesday made as strong a case as can be imagined for a U.S. presence on the global design stage.

“It’s just a pair of flat-front trousers and a T-shirt,” Cox said backstage before the show.

Yes, but the trousers had a 48-inch waist and were stitched by an old-school tailor in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and the T-shirts were of see-through organza with sleeves meticulously pick-stitched for a rumpled Stanley Kowalski effect.

With their pants cinched tight at the waist like the throat of a moneybag, their wide trouser legs flowing, their narrow chests visible through transparent shirts and bombers, models like 17-year-old breakout star Charlie James or newcomer Charlie Ayres-Taylor appeared to glide down the runway. A lot has been made lately of androgyny and a so-called trans moment, and designers here and in Europe have shown menswear collections on models of either (or neither) sex.

For all the malleability of the Duckie Brown designs, the ideas they proposed seemed less concerned with gender blur than with shape and proportion, drama of movement, the volumes displaced by a body shifting through space. It is not that the designers are unmindful of gender issues so much as that they brush right past them in an effort to create clothes with some of the same metaphorical concerns sculptor Do-Ho Suh evinces in the ethereal transparent structures he builds from mesh.

“Am I not a real man because I wear a chiffon blouse?” Cox asked, rhetorically.

Oddly enough, the clothes were assertively masculine in at least one sense, that of manspreading. A fellow in a pair of 48-inch-waist trousers, after all, takes up a lot of room.

Anchoring the creative flights at labels like Duckie Brown in a more recognizable reality were designers like Michael Kors, Todd Snyder, Tomas Maier and Dao-Yi Chow and Maxwell Osborne at Public School. All made strong cases for recognizing one too-little appreciated fact. That is, U.S.-style sportswear – more specifically, California-style sportswear – probably exerts more influence than any other single factor on what men around the world put on their backs.

Kors expressed this straightforwardly enough at a Wednesday morning presentation that recast the basics of a classic sportswear wardrobe (bomber jacket, cardigan, short pants, hoodies, anoraks) in fabrications like paper-thin lambskin, Inox cotton, bonded suede – stuff materially or technically refined enough to merit being marketed as luxury goods.

“My family lives in LA,” said the designer, who personally walked editors, buyers and critics through his collection with the wisecracking wit that made him a reality TV star. “And if LA taught the world one thing, it’s ‘I love it, but can you wear it with jeans?’”

The aquatic palette of the Kors collection derived from annual visits the designer makes to Capri, that small rocky island off the coast of Naples so beloved of the emperor Hadrian and of every fashion designer that ever tossed a pastel cashmere cardigan over his shoulders.

Snyder also made references to Capri in a relaxed collection, one that favored shorts suits, soft shoulders, linen tuxedos the color of denim, officer shorts, terry cloth polos, suede fatigue jackets and – in what seemed like a radical gesture in an era of open-necked shirts for the open workplace – even suits worn with a tie.

The attitude he was aiming for, Snyder explained, was of sprezzatura, or the offhand elegance Italian men labor so strenuously to attain. The palette derived from the Mediterranean, which the designer referred to in show notes as an ocean.

It hardly mattered. Relatively few of us are likely to be found enjoying a Negroni on the terrace of the Hotel la Scalinatella on one of those cool Capri evenings that, as Kors pointed out, practically demand a chambray cashmere cardigan.

For his part, Thom Browne once again proved himself a gifted scenarist by showing a collection of gray suits (many with short pants and modified frock coats) in a mirrored box in a basement studio on West 27th Street.

Viewers queued up to enter this office space, with its chromed desk and chrome desk fittings and infinitely multiplying images of models that look chosen from an Identi-Kit wearing shades of gray, and then wandered around slightly dazed by the surplus of reflectivity.

As an act of manipulation, it was masterful if vaguely dystopian, in a Terry Gilliam kind of way. Possibly the designer was editorializing on the toxic solipsism of the selfie era, since there is nothing like being trapped in a room with your own reflection multiplied a thousandfold to send you screaming into the arms of anonymity.

As it happens, Browne is not the only designer with a taste for esoteric tableaus. Tar-beach types are as interested as jet-setters in looking good, and for those of us who summer where we winter, there is Public School.

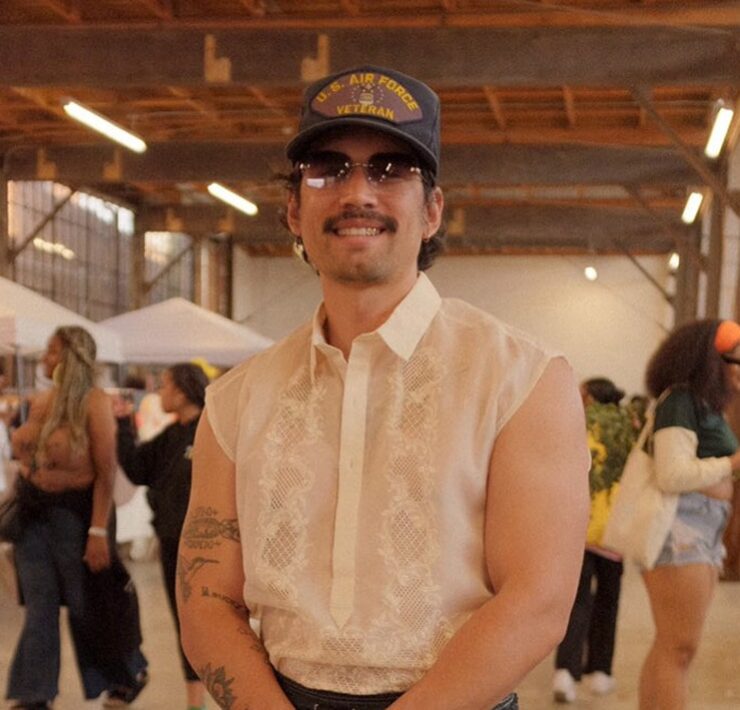

In enclosures resembling lineup rooms at a police station, Public School presented its spring 2016 collection. Within each room, men including Wooster; actor and designer Waris Ahluwalia; singer, producer and writer George Lewis Jr. (known as Twin Shadow); and a posse of popular models like James, Piero Mendez and Adonis Bosso were up against the wall.

Clever as the idea was it, too, made for difficult viewing. Among the kinks that remain to be worked out in the nascent New York Fashion Week: Men’s is what format is best for showing men’s clothing. “See it first!” one sharp-elbowed Instagram hound said, as he jostled aside singer Joe Jonas to get into smartphone position. “Get a ‘Gram of it! Team early! Hashtag TeamEarly!”

If in fact the Public School designers were after serious critical consideration, it is possible #TeamEarly was doing them no favors. A prevalent fallacy of the hyperdemocratized world of the Web holds that the image is all-sufficient; certainly the Public School presentation made for plenty of great Instagram moments.

Yet there were rewards to be gained from close repeat viewing of a collection that built on the designers’ continuing experiments in marrying elements of formal tailoring to familiar streetwear silhouettes; in the way they layered sleeveless tunics over shorts; cropped the sleeves of a jacket to an elbow length familiar from ballplayers’ throwback uniforms; made a squared-off jacket whose lapels descended to a series of covered buttons

What Public School probably does best is to produce a new kind of uniform. It is one that requires no particular translation for a generation of young wearers whose style icons growing up tended to not to be the politicians or power-suited business moguls their fathers looked to, but pro athletes, hip-hop musicians and the guys we all see on the subways, men whose saggers, muscle T-shirts and crisp monotone generics lend them an ineffable cool that, if not in every case innate, is assuredly borough-bred. NYT