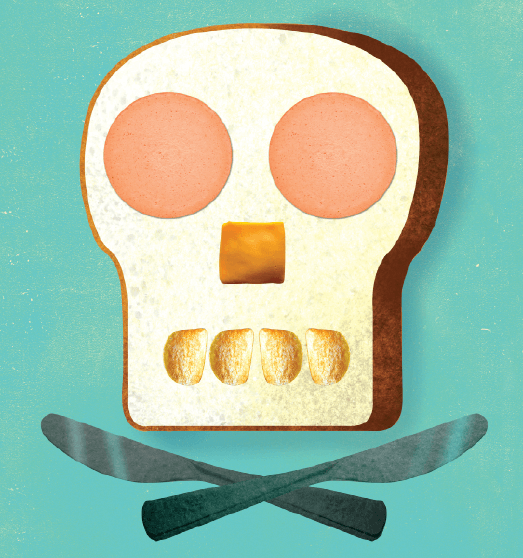

Why everything is bad for you

When I was growing up in the same New Jersey suburbs so expertly described in Todd Solondz movies and Tom Perrotta novels, the usual lunch for me was a sandwich consisting of Wonder Bread spread thick with Land O’ Lakes butter, a wad of Oscar Mayer bologna and a slice of American cheese.

The beverage was whole milk, Tang or Coke. A stack of salty Pringles rounded off the meal.

Even if I had known back then that people who eat a lot of processed meat tend to die of heart disease or cancer, and that processed cheese is held together by emulsifiers that may lead to kidney problems, and that white bread has almost zero nutritional value, and that soft drinks are sludge, and that Pringles may not qualify as potato chips, I wouldn’t have cared. I had a lot on my mind, what with school and all the playing, and I had yet to develop the fear of death.

But now that I’m an adult who apparently has nothing better to do than bathe in the light of computer screens 16 hours a day, I have plenty of time to scroll through articles eager to persuade me that food is killing me.

Like everyone else, I believe every word in those articles. And when my gaze reaches the fifth paragraph, the one that inevitably quotes the university professor who has conducted the latest fear-inducing study, I nod slightly and tell myself that somehow I knew it all along, that I always had a feeling that this meat, or that vegetable, was quickening my demise.

Which is strange because at the same time, I believe that food is keeping me alive.

We’re all going to die. And we all eat food. Therefore, food must be the culprit.

That seems to be the absurd syllogism that lies beneath the surface of many stories in the health, food and science press.

By now we can recite the list. Too much red meat may lead to stroke, cancer and heart disease; until this year, chicken sold in supermarkets may have included arsenic; and even small amounts of pork, when undercooked, can give you trichinellosis, which is no picnic.

Fish that live high on the food chain, the especially delicious ones like king mackerel and tuna, may contain mercury, which leaves us with little choice but to order the squishy creatures at the bottom of the sea, like clams, oysters, mussels, cockles, lobsters, crabs and, don’t forget, those tasty periwinkles.

But while some health advocates are gung-ho about the bivalve shellfish, others remind us that they tend to soak up toxins, viruses and bacteria that may afflict people who eat them with three types of shellfish poisoning. The toxins that cause the poisonings, furthermore, “are not destroyed by cooking,” the Canadian Food Inspection Agency warns.

So there’s that.

Fruits and vegetables in general present a dilemma: the ones that are commercially grown may include pesticides linked to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; the organic variety may be no better, according to a Stanford study that found “little evidence of health benefits” for those with an organic diet.

Like those federal agents who brought down Al Capone on a charge of tax evasion, we are not above indicting certain food items for reasons having nothing to do with the health risks they may pose. Almonds, for example, are packed with protein, but if you imagined that you could eat them without compunction, you are not familiar with an article in The Atlantic, “The Dark Side of Almond Use,” by Dr. James Hamblin.

He reports that a single almond soaks up 1.1 gallons of water before he goes on to argue, quite persuasively, that anyone who eats this tree nut exacerbates the disastrous ecological conditions brought on by the drought in almond-rich California.

Salad eaters are perhaps equally numb to environmental concerns, according to a recent Washington Post article, which makes the case that the lettuce crop takes up too much arable space for the nutrition it delivers.

Even water has become a target. Recent articles point out that drinking eight glasses per day, long thought to be a good idea, is a fool’s game, and that too much water can kill you.

Such stories stick in the mind because of their inherent irony: The very things that provide us with sustenance, they seem to argue, may be out to get us.

I hope you don’t mind the idea of dining on dung beetles, caterpillars and locusts, among other such critters, because that’s what the United Nations recommends in an exhaustive report. We need to get over our aversion to entomophagy, its authors argue, if we are to survive on an overpopulated planet wracked with climate change.

Cooks.com, jumping on the bandwagon, offers a recipe for a protein-rich dish, earthworm chow.

Another foodstuff of sorts now considered less of a problem than, say, meat, is dirt. Actual dirt. Until recently, the practice of eating it was classified as pathological. No more. It turns out that geophagia is widespread, relatively harmless and may protect the body from toxins.

Health-scare stories, even those that are not overblown, draw their special power from the fact that we go through the days denying our mortality. Each one reminds us anew that there’s no way out.

Unable to avoid this tragic and absurd-seeming condition, we lash out against our fates by finding fresh reasons to make a villain out of the one thing that is doing its part to keep us alive: food.

We add salt to the psychic wound when we momentarily trick ourselves into believing that bugs, worms and dirt are the only things fit for human consumption.

I’m not falling for it anymore. I’m going back to bologna and cheese. NYT