Travel diary: Exploring Bukidnon, the cowboy’s country

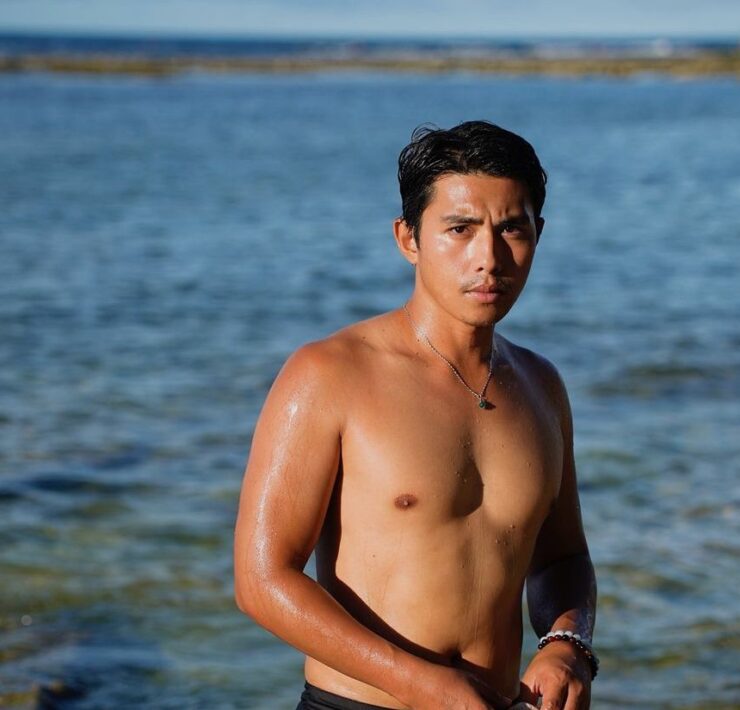

The pineapple fields stretch out into the horizon, their green and yellow spiky stalks reaching up and out in acceptance of the midday heat. The Land Cruiser raises brown dust in its wake, but despite its speed, the mountain ranges still loom miles away.

We’re on our way to the Tuminugan Nature Sanctuary in Sankanan, a 64-hectare property located at the foothills of Mt. Kitanglad. Our “guide,” Paula Perrine, a tall Caucasian-looking woman who nevertheless was born and raised in Bukidnon, points out the stretches of greenery that cuts through the Del Monte Philippines, Inc. plantation. “It’s hard to believe but in those parts, the land dips down into ravines.” The 25,000-hectare plantation at the Manolo Fortich municipality, it turns out, sits atop a high plateau bordered by the mountain ranges that we seem to see everywhere we turn.

Bordered by Misamis Oriental in the north, North Cotabato in the west, Davao in the south, and Agusan del Norte in the east, Bukidnon is cowboy’s country, a landlocked mass where much of Region 10’s food is produced. And while it is nowhere near the sea, the province is basically the water source of all of Mindanao, housing the region’s major rainforest watersheds; the Mt. Kitanglad mountain range supplies water to the six river systems of Northern Mindanao.

Bukidnon is still known to most as the land of pineapples, but with dedicated locals working on developing what the place has plenty of to offer, it is on the verge of what could be a massive tourism boom—not exactly the kind of boom that Cagayan de Oro has experienced, with its franchise malls and commercial developments, but something more authentic to the county’s rugged beauty.

The Perrines are one of those locals. Related to of the Fortich-Azcona clan, whose patriarch Don Manolo was Bukidnon’s first governor, they switch with ease from Bisaya to English to Filipino even as their fair skin, sun-kissed hair, and aquiline features speak of Western roots.

Like something straight out of a fairy tale

We’ve finally reached the sanctuary, which John Perrine bought in 1975 when it contained nothing more than browned grasslands, a clump of bamboo, and a solitary avocado tree. Today, it has a dense arboreal paradise that boasts a mix of hardwood and fruit-bearing trees. It surrounds a sizable clearing that holds picturesque pastures, a coffee plantation, nurseries for giant bamboos and red calliandras, vegetable and flower gardens, and a mid-sized house that can be rented as a B & B. “He started with 12 species of ficus trees, acacia, narra, mahogany, bangkal—basically, he was like Johnny Appleseed,” says Renée Araneta-Perrine of her husband’s early reforestation works. She directs our attention to the giant acacia tree towering over the house. “That tree is around 30 years old; ferns, moss, orchids, and other ficus have grown on its trunk.”

Perrine’s decades-long work on the farm, when condensed into a simple story, seems like something straight out of a fairy tale: once the trees started to grow, the birds and bats came, which furthered the pollination and seed dispersal process. As the trees grew in number, so did the local fauna; as if from nowhere, water springs also appeared in the property, and rainfall became more regular in the area. “Even during the last El Niño season, it rained here at least once a week even when it was bone dry just 200 meters away from the farm,” says farm manager Neil Binayao. “Late in the afternoon, you can see the mist rising from the forest.” A recent bird inventory in the property reported 64 documented species, some migratory; there are wild deer living in the woods, along with bats, civet cats, snakes, and monitor lizards. The forest’s floor area has also increased and gotten denser with natural growth. “It just shows that if you build it, they will come; nature eventually takes over,” Binayao remarks. The place is now a far cry from the dry, desolate land that Perrine had discovered, a photo of which is kept on the wall of the farm home.

Sunny mornings, cool afternoons

Complementing Bukidnon’s fecund soil is its temperate climate, two prime reasons why an American pineapple company deemed it ideal for its massive plantation back in 1927, and why the province continues to hold its status as the food basket of Mindanao. “What people can expect here are sunny mornings and rainy afternoons,” Paula Perrine affirms. “Though it can be warm during the day, it gets quite cool when evening drops.”

The topography is also varied enough to marvel visitors and recall to mind other exotic faraway places: the rolling terrains, New Zealand. The rain forests, the Amazon. The wide grasslands, the South African savannah—all of them just minutes of driving away from each other. “I used to bring guests to this beautiful spot with a view like The Grand Canyon,” Perrine recalls; from a vantage point at the national Sayre Highway, the Canyons Mangima and Tagoloan can be seen. “It was so wonderful to see especially in the morning.” The view has since been marred by big electrical towers.

Raw and rugged beauty

With adventure camps beginning to attract tourists through the more immersive experiences they offer, Bukidnon’s “raw” aesthetic becomes more valuable in an eco-tourism-centered promotion. Kampo Juan and Dahilayan Adventure Park, both located at Manolo Fortich, bank on the province’s pristine views and lush vegetation for its adrenaline-pumping activities such as the anicycle (at the former) and the dual zipline (at the latter). About 25 minutes away, Bukidnon’s tribal capital Impasug-Ong, home to indigenous peoples and a rugged terrain of gorges, canyons, and mountains, is also home to the Center for Ecological Development and Recreation (CEDAR). Here, a 373-hectare part-man-made and part-natural forest is open for guided eco-walks. At the serene green waters of Lake Apo in Valencia City, floating bamboo huts are available for rent to those who want to navigate the circumference of the crater lake, which has a depth of about 85 feet. These are just the moderately developed tip of the iceberg of what Bukidnon has plenty to offer.

“I think this is the best time for people to come and experience the place, when it isn’t crowded or too developed yet,” Perrine says. We concur: with the Malaybalay city proper housing only a few hotels, it isn’t exactly five-star luxury tourism that will raise Bukidnon’s stock, but something more suited to its earthy, breath-taking beauty.

On the drive back from Sankanan to Dicklum, the late afternoon light bathes the pineapple fields in soft yellow light. Field workers are gathering the suckers and shoots, left behind after the harvest.

It’s as beautifully rustic a scene as any Amorsolo masterpiece.

This story originally appeared in the June 2013 issue of Garage Magazine.